Ola ka honua

A Jilli Rose film inspired by the Auwahi project, Maui, Hawai’i

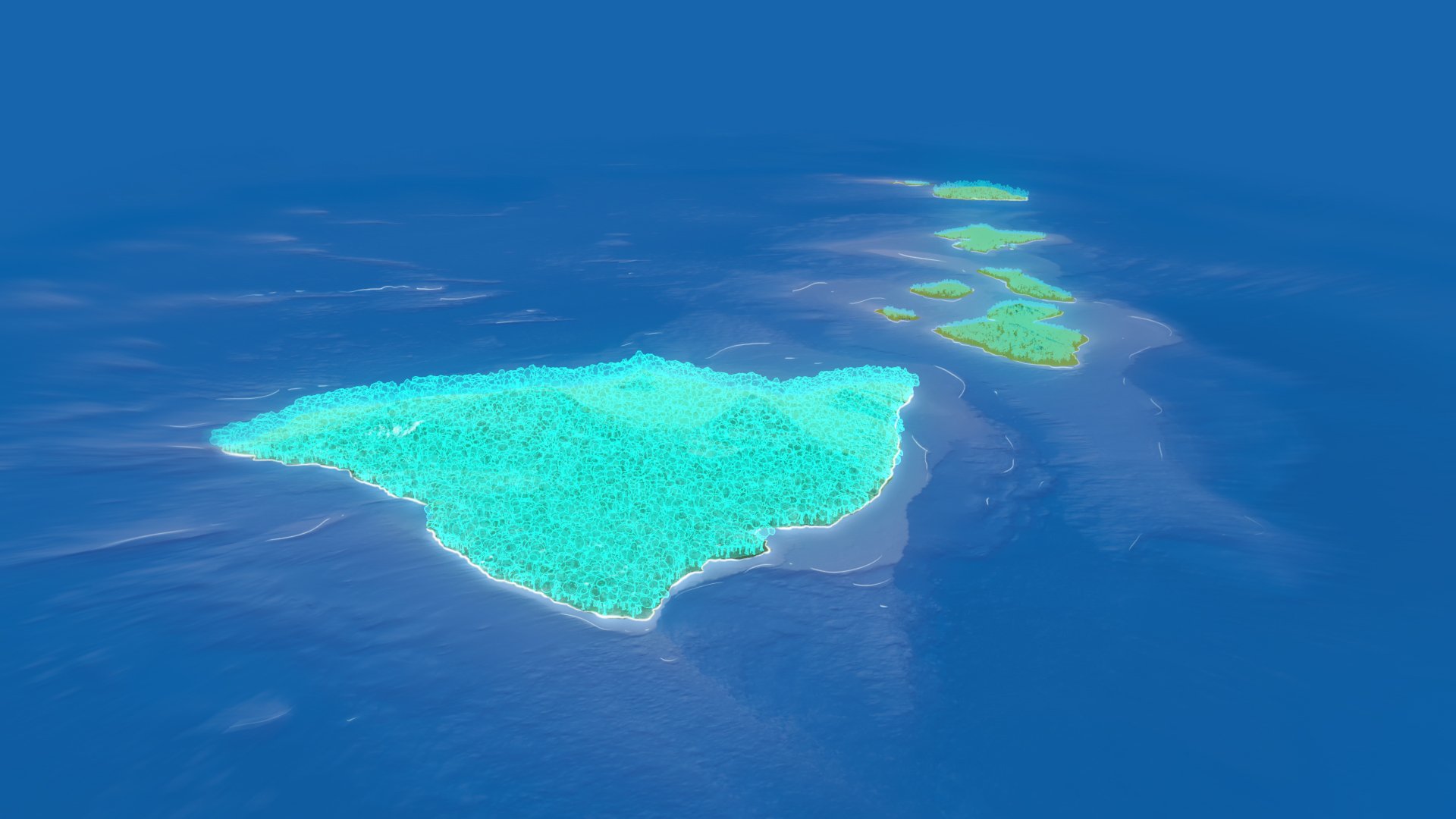

Once the Hawaiian Islands were covered with forests that were the home of a kingdom of plants and birds found nowhere else on the planet. Separated away from all other land sources, life evolved anew – almost as if all of earth’s life was recreated again on another planet.

With the arrival of Europeans, Hawaiian forests and native Hawaiian culture had similar fates – they faded and wavered at the edge of existence. First years - then decades - then centuries slipped by, until the land became filled with new arrivals, first a few, but now to near capacity, the islands’ natural systems stressed to their limits. A question with great consequences to the future of Hawai’i rose to the forefront - could native forests, fundamental to the Hawaiian culture, that once cloaked and protected the islands be brought back or were they lost forever?

The film ‘Ola ka honua’ frames a series of questions. Can native Hawaiian forests, sliding backwards over for centuries, return? And, can humans assist as stewards? And what of the special role that native Hawaiians, keiki o ka ‘aina (‘children of the land’), the most impacted of shareholders, can play in this healing?

Ola Ka Honua is a short film animation released this year by internationally recognized, award-winning, Australian film producer Jilli Rose inspired by forest restoration at Auwahi, Maui. The film has recently premiered in film festivals in New Zealand, Australia, Canada, Portugal, Portland (USA), with its first local premiere this month at the Hawai’i International Film Festival.

Ola Ka Honua won the Best Australian Short Documentary at the prestigious Antenna Film Festival in Sydney, Australia and has been nominated for an award at the Hawai’i International Film Festival. The Antenna Film Festival described Ola Ka Honua as, “A story beautifully developed around the crisis of deforestation in Hawai’i, Jilli Rose’s animated documentary combines cultural history and science to bring the past into the present, emphasizing the status and value of trees as living treasures. Cleverly structured and perfectly paced, the film evokes a devastating history, then transcends it with optimism and hope for the future.”

Jilli has captured the Auwahi story in a unique and deeply personal way – she tells Hawai’i’s story of tragic loss of native forest through an artist’s eye. With original score by Kristin Rule, Ola Ka Honua shares the story of the rebirthing of native watershed forest on a working cattle ranch by a community that cared and by a landowner, Ulupalakua Ranch, who took an uncommon stand.

Watershed forests, wao akua, literally ‘God forests’

Hawaiian watershed forests are our only source for essential fresh water that is the life blood of isolated, highly populated islands. The economic value of these watersheds is nearly incalculable, as they not only receive, filter, and store water resources, but also moderate flood events and reduce topsoil loss due to excessive erosion. Hawaiian watershed forests also provide the only remaining habitats for numerous species of endemic plants, birds, snails, and insects. Culturally, these ancient forests are in Hawaiian cosmology, considered wao akua, literally ‘upland areas of the Gods’, revered for their spiritual value, as well as for animal and plant material that are important components of Hawaiian ethnobotany and cultural protocols.

Can degraded and lost native forests be returned?

We are entering unprecedented times in Hawai’i with circumstances distinct from anything that has happened in the past, testing the capacities of our existing social and ecological systems. Today, born of care for future generations, new questions are being raised here in Hawai’i about the potential for a more sustainable, more productive relationship with our natural environment.

The greatest return on investment in ecosystem management appears to be the protection and restoration of critical, regulating components of our natural world, such as coral reefs and mauka watershed forests. Efforts in these key areas promote ecological resilience at the landscape level, moderating disturbance impacts rather than letting them run.

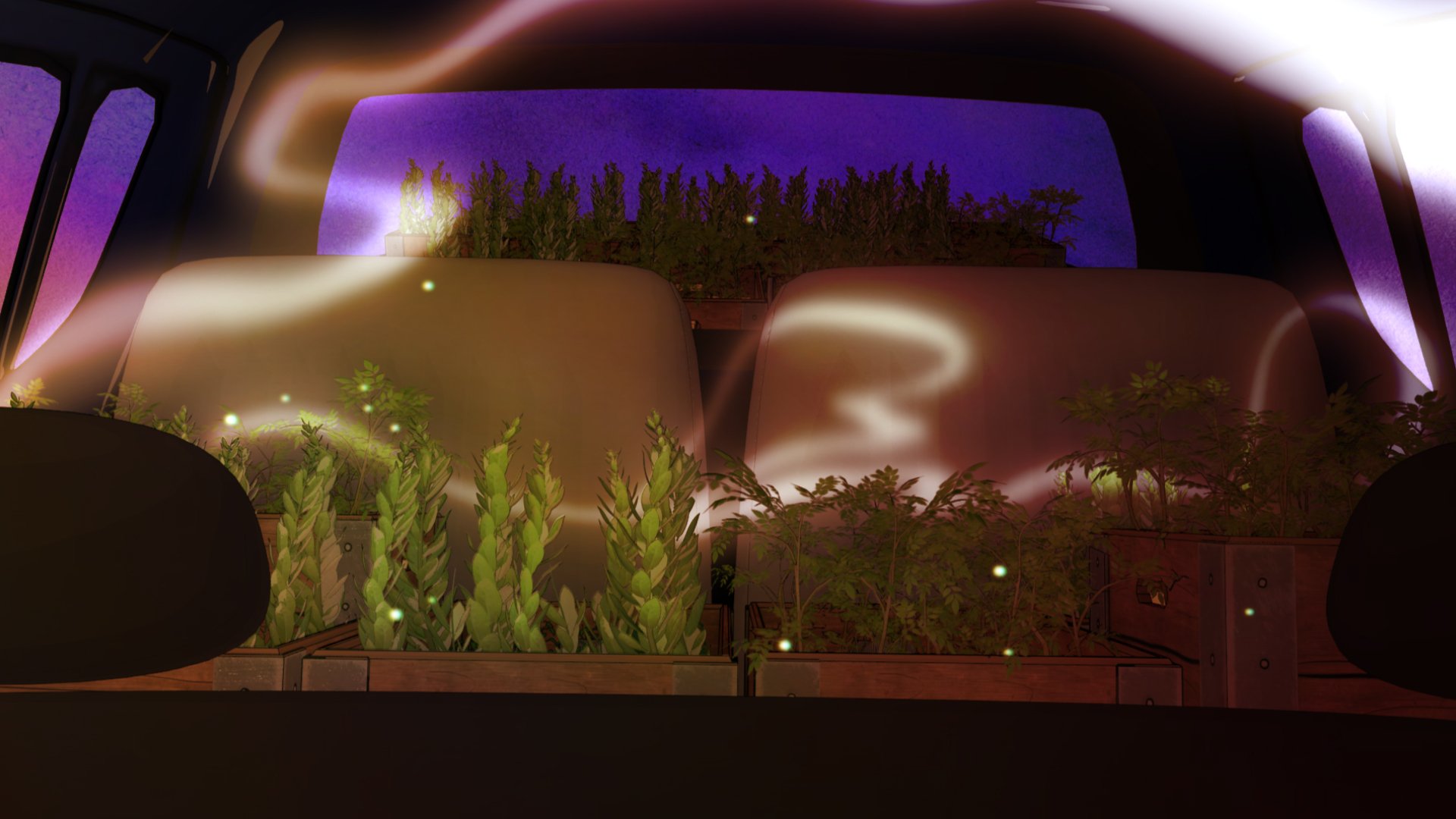

Started 25 years ago, the Auwahi project (www.auwahi.org) was the first attempt on Maui to see if restoration of damaged native watershed forests was even possible. In some ways, the results at Auwahi changed everything, shifting paradigms surrounding native forest restoration in the islands. After an absence of hundreds of years, a diverse suite of native trees of Auwahi naturally began producing seedlings again, for restoration ecologists, like hearing a faint heartbeat. Auwahi was an attempt to try everything possible to save forest being lost, just as in the care of a loved family member.

The progress at Auwahi in field-to-forest restoration is perhaps more meaningful, and certainly more durable in that it was done primarily with community volunteers. Now, 25 years later, with the help of people, the forest has rewoven itself all the way to the extents of the fences protecting the forest restoration areas, creating ‘green squares’ of forest from pastures, small flagships of successful collaborations between humans and the natural world, one community-based solution for a troubled world.